World of watches

A strict head timer and a precision watch

By Peter W. Frey

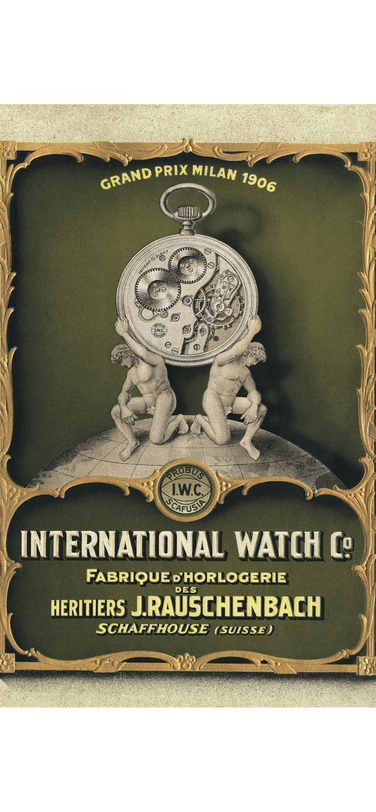

Two burly young men kneel on the Earth’s northern hemisphere, bearing a pocket watch on their shoulders. Below or above runs the legend “Grand Prix Milan 1906”. The motif recurs in IWC catalogues and notices until well into the 1920s. A further reference to the triumph at the Milan Universal Exhibition of 1906 is engraved on the backs of pocket watch cases.

World fairs came into vogue in the second half of the 19th century. They were important platforms for industrial achievement and popular showcases of technical progress. After the “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations”, staged at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, a further 40 such events were held in Europe, the USA and what was later the Commonwealth of Australia, up to the outbreak of the First World War.

IWC’s first recorded presence at an international exhibition was in Sydney, New South Wales, in 1879. Watches from Schaffhausen then went on to win prizes at many exhibitions. The “Grand Prix” at the 1906 Esposizione Internazionale del Sempione was one of the high points in a long series of accolades. Clearly it was an exceptionally prestigious prize. The Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce reported the names of the Milan winners thus: “Joint winners of the gold medal: J. Häberli, J. Vogel and Urs Hänggi.”

Watch technician Johann Vogel and entrepreneur Urs Hänggi, both natives of Solothurn, are prominent names in the history of IWC. The pair were recruited by Johannes Rauschenbach-Schenk, whose father had died in 1881, obliging him to take over the management of the watch factory at the age of 25. Another figure, who has received less attention to date, is Johann, alias “Jean” Häberli. He came to Schaffhausen as “chef régleur”, or head timer, likewise at Rauschenbach’s invitation, in 1893.

—Jean Häberli and his wife in Langenthal, pictured here by photographer Jos. Gschwend

The son of a humble watch industry worker from Reconvilier, in the Bernese Jura, Häberli had learned the craft from the bottom up. He was to gain a reputation as a skilful timer at the then Seeland Watch Company in Madretsch, near Biel/Bienne. “I presented myself in Schaffhausen as a 38-year-old man bursting with health,” narrates Häberli in his handwritten memoirs, a later copy of which fills more than 160 closely printed pages.

Häberli penned his recollections shortly before his death in 1929 for his 13 children, as he himself explained. The jottings represent an interesting source of social and industrial history in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Above all, they provide a fascinating insight into the work, the disagreements over technical issues and the human conflicts in the IWC offices and workshops at the time.

As head timer, Jean Häberli was responsible for the accuracy of watches leaving the factory. This was a far more complicated task back then than nowadays. There were no electronic measuring instruments to indicate immediately whether the balance had the correct amplitude, whether the beats – or semi-oscillations – it produced were of the right duration, or how many seconds per day the watch was running fast or slow in the various positions tested. The only control references at Jean Häberli’s disposal were a precision pendulum clock, or a pocket watch. The rest was a matter of knowledge, experience, deft fingerwork and intuition.

—Jean Häberli was responsible for the accurate timing of watches leaving Schaffhausen. Like this Lépine open-face watch with a 52-calibre movement

IWC never entered specially prepared watches for chronometry competitions. But the factory regularly consigned large numbers of pocket watches for accuracy testing by various observatories, in Neuchâtel and elsewhere. The test certificates often bore the remark “specially good results”. Jean Häberli’s memoirs for 1895 proudly recount, “It emerged that two of my timepieces had won prizes as the best of the whole year.” Three years later, he recorded, “In addition to my other Herculean task, I have made 171 chronometers with test reports from Neuchâtel and Geneva.” Watches observatory-certified as accurate attracted a “premium quality” markup in the trade.

Jean Häberli was confident in his own abilities. His memoirs never leave any doubt what he thought of certain employees and managers. “I saw that the technical foreman was incompetent,” he notes in his introductory discourse. Scathing with equal facility in French and German, Häberli repeatedly refers to staff members as “blagueurs” (jokers), “filous” (rogues) or “traurige Finke” (pathetic so-and-sos). He set the highest standards of accuracy for the IWC watches in his charge, and had no patience with half-measures. “I had no use for such a person, who fell asleep while eating,” he explains in an entry for 1898. He notes about a whole group in the workshop, “I was perfectly blunt with them. Do as I tell you, or get out.”

—For many years, the 1906 Grand Prix Milan adorned IWC’s catalogues

Häberli comes across as a patriarch, but the longer he worked at IWC, the stronger his impression became that the management did not wholly appreciate his skill. “A sense of injustice wormed its way deeper into my heart,” he records in 1908, two years after the Milan “Grand Prix”. He took it as a mortal insult that the gold medal for the Milan success was withheld from him. He tendered his resignation, but signed a new contract the next day with the firm “to which I had grown so close.”

So close, indeed, that around one-third of his extensive family was employed at one time or another by IWC. The staff register of the era, displayed at the entrance to the IWC Museum in Schaffhausen, lists not only Jean Häberli but his two sons, Hans and Ernst, and his three daughters, Marie, Alwina and Mina. Ernst Häberli, born in 1886, followed in his father’s footsteps. After serving an apprenticeship at IWC, he attended the Neuchâtel School of Watchmaking from 1907 and became head timer at IWC in the 1920s.

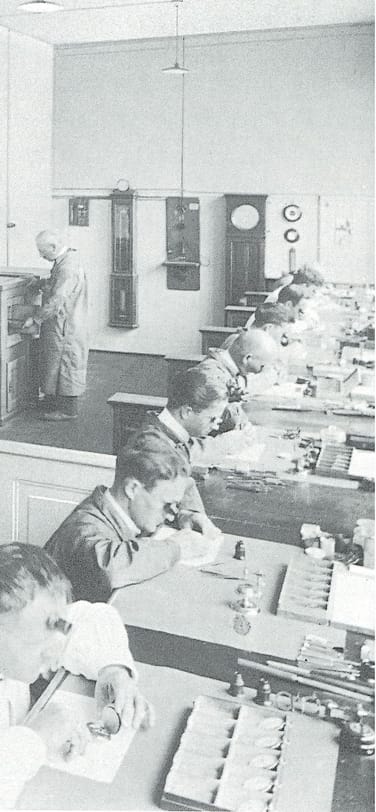

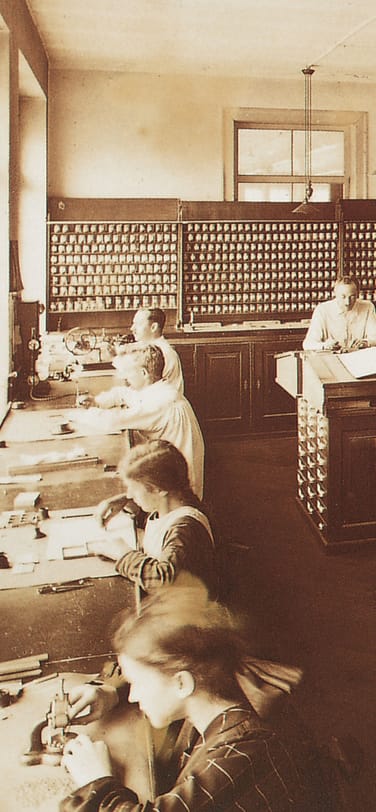

—A view of the workshop at IWC in 1924. Timers carry out one of the most demanding jobs during the assembly of a watch movement: the adjustment of the balance spring until it runs true and flat

Jean himself was reluctant to quit and was pressed into retirement at 67, under threat of dismissal. “What was I to do?” he wonders, in his memoirs. He felt that continued refusal to resign would have imperilled the positions of his relatives at IWC. Erich Häberli, Ernst’s son and Jean’s grandson, remembers that the family version of events was always that grandfather had only agreed to resign on condition that his son Ernst should succeed him.

Apart from Ernst, none of Jean Häberli’s plentiful offspring remained loyal to the factory. However, four generations later, a descendant of IWC’s former head timer is again an employee of the company. Yvonne Caillet has worked in movement assembly for 18 years, where she assembles movements of the 5000-calibre range. It only first truly dawned on her that she was related to a well-known IWC watchmaking personality when she looked in the showcase with the staff register and saw a picture of Jean Häberli’s daughter Mina: “That’s my great-grandmother!” Which makes Jean Häberli her great-great-grandfather.

—Jean Häberli’s daughter Mina also worked for IWC Schaffhausen