World of watches

WHERE TIME FLIES

By Manfred Fritz

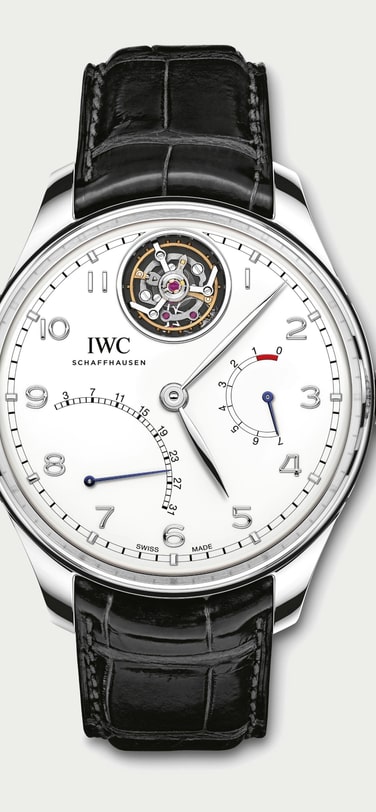

Ask watchmakers, and one thing is soon clear: their favourite complication is the tourbillon. At the same time, it is one of the most demanding. Strictly speaking, the mechanism is something of an anachronism today. And the “flying” tourbillon, a particularly refined version of this watchmaking delicacy that can be found in the Portugieser Tourbillon Mystère among others, does not really take off. Which would, of course, be a pity. But it does present the delicate mechanism in its most fascinating form, as connoisseurs are well aware. For them, there are two types of watch: those with and those without a tourbillon. The objects of their desire come to life in IWC’s small, but exclusive specialities department, whose windows look onto the Rhine gliding slowly by.

Here, master watchmakers like Hansjörg Kittlas assemble tiny parts that are barely visible to the naked eye to create living mechanisms that are genuinely among the most beautiful objects ever created as part of the fine art of watchmaking. And which, in view of the enormous amount of manual craftsmanship involved, remain very rare. Take the example of IWC: of Kittlas’s colleagues, only two others master the supreme disciplines. These also include the minute repeater, the Portugieser Sidérale with its constant-force tourbillon and the Grande Complication.

But, above them all is the tourbillon, a small, rotating and pulsating assembly that is no longer hidden away behind covers but on show for the world to see. It is steeped in legend and poses several questions. Are watches with a tourbillon better? Why are they so valuable? Do they protect the movement from the influences of gravity? Let us try to answer these questions one at a time.

The tourbillon is a makeshift solution to which Parisian watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet resorted in 1795, because even his pocket watches had an annoying tendency to show the wrong time. Which was not a recommendation for the acknowledged master of his metier. But while other manufacturers sought ways of correcting the fault through materials and production methods, Breguet looked for an alternative solution. And found one.

But first, a little theory. Ideally, in a watch escapement, the balance spring and the balance are in perfect poise, which means that the centre of gravity is exactly in the middle of the balance staff. At Breguet’s time, the main problem was errors in the centre of gravity in the balance spring and the cut balance rim. Rate fluctuations in various vertical positions caused by the effects of gravity all add up.

Breguet realized that he would not be able to eliminate the problem with the means available to him then, but he could at least compensate for them. And that is where the ingenuity of his idea lies. He mounted the entire oscillating system and escapement, comprising balance rim, balance spring, escape wheel, and pallet lever, on a base in a delicate steel cage. The arrangement was bearing-mounted at top and bottom, and the watch’s wheel train caused it to complete a full rotation every minute.

This alone, of course, was not enough. The actual escapement in the cage also needed to be powered. To achieve this, the fourth wheel, which normally drives the escape wheel, was mounted below the cage and secured to a bridge. The elongated pinion of the escape wheel passes through a hole in the (rotating) lower section of the cage and engages with the teeth of a fixed fourth wheel. It then practically revolves with the cage around this wheel. This arrangement ensures that, in addition to the rotation of the cage, the escape wheel, pallet lever, balance spring, and balance also move inside the cage. And in this way, Breguet overcame the force of gravity.

Because during the first 30 seconds of the minute, the watch would run too slowly; it would then run too quickly by the same degree during the second 30 seconds and compensate for the irregularity. First unveiled in 1795, the mechanism was granted patent protection in Paris as a “Régulateur à Tourbillon” in 1801. The word translates as “whirlwind”, and with the various sequences of movements of the cage and escapement, this attractive image comes very close to describing it.

At the same time, from a watchmaking point of view, working on the delicate mechanism is akin to open-heart surgery. It is a case for absolute specialists. Even now. The watchmaking complication par excellence has been subject to ongoing modifications. One of these can be attributed to the head of the Glashütte watchmaking school, Alfred Helwig. In 1920, he found that the bridge with the top bearing, which was mounted above the tourbillon cage, seriously impeded the view of the mechanism. So, he relocated the mounting to the underside of the bottom of the cage.

Helwig’s invention has since been known as a “flying” tourbillon because it appears to hover in thin air. It is, of course, an illusion. IWC’s design engineers took the idea a step further in the Portugieser Mystère. Here, they made the lower section of the cage, whose outer teeth engage with a tourbillon pinion, out of tempered, black, anodized light metal. The entire cage then rotates in a stable sapphire ball-bearing, which means very low friction. This permanent “air show”, for want of a better term, thus takes place openly against a jet-black background: a “black hole”, as one watchmaker graphically described it. It measures 11 millimetres in diameter. And almost magically attracts inquisitive glances.

In IWC’s specialities department, the equivalent of watchmaking’s Formula 1 takes place on a daily basis. Except that it is extremely quiet and demands infinite patience. Hansjörg Kittlas and his colleagues literally plunge themselves into the narrow passageways and endshake between wheels, pinions, screws and springs. Using their tweezers rather like cranes, they position individual parts where they belong, test their functions, and, where necessary, file and polish them.

The tourbillon, which has 82 parts and tips the scales at just 0.653 grams, is assembled separately on a small bridge.

If needed, ultra-thin gold washers are mounted under the weight screws to ensure perfect poise in the balance. The Breguet spring, with its bent overcoil, is secured in place, the pallet lever and escape wheel are positioned, and the cage, made of steel, is mounted. The same watchmaker also assembles the actual movement, a 51900 calibre. The most exciting and satisfying moment, according to Kittlas, comes when the finished tourbillon and the watch engage with each other for the first time: in other words, when power from the barrel and wheel train is connected, and it runs. After this, the entire mechanism is dismantled, oiled and re-assembled. The entire process, including casing-up, is the sole responsibility of one person.

The extra-large 51900 calibre oscillates at a rate of 2.75 hertz. With a Pellaton winding system featuring ceramic pawls, a solid gold winding rotor and blued screws, it is part of the company’s thrust to make a series of new, in-house movements. The seven-day power reserve is an advantage in this watch when we consider the retrograde date display. The fact that it ultimately performs better, even if the tourbillon in a watch powered by movements of the wearer’s arm has forgone its original function, is clear. Because it is, down to the tiniest detail, the work of a true master with many years of experience. There is no longer a formal limitation for this exclusive speciality. The work alone makes it limited.

So let us ask the question once again: why does the complication still exist today? As explained: there are watches. And there are watches with a tourbillon.

The rarity factor alone means that the chances of seeing one are about as high as the probability of meeting a Siberian tiger on the Fronwagplatz in Schaffhausen. As for the Portugieser Tourbillon Mystère, the positioning of its most exclusive feature as a “living twelve” on the stage provided by this 70-year-old classic is a feast for the eyes. To put it another way: the tourbillon’s practical functionality ceased to be an issue long ago.

Hansjörg Kittlas, who spends his free time with much larger machines, such as his high-performance BMW, somewhat mischievously puts it like this: “There are some people who sit down in front of an aquarium at home because they find it relaxing. Looking at a tourbillon can also be a way of bringing peace and quiet to your life.”