World of watches

PUTTING ETERNITY ON YOUR WRIST

By Boris Schneider

Read Time: 6 min

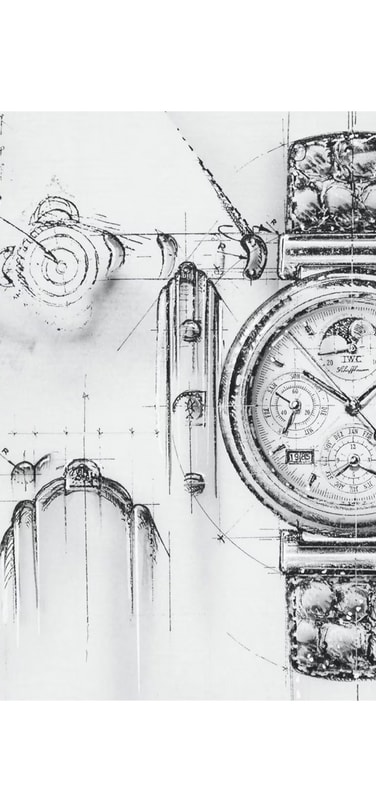

During his time as head watchmaker at IWC, Kurt Klaus translated the Gregorian calendar with all its many irregularities into a mechanical program that will continue running perfectly until 2499 with virtually no corrections from outside. His legendary design was first featured in the Da Vinci Chronograph Perpetual Calendar in 1985 and is still regarded, even today, as a milestone in the art of watchmaking. Of ingenious simplicity, and with a total of just 81 parts, the calendar took the luxury watch manufacturer from Schaffhausen to the peak of haute horlogerie.

“Sometimes you’ve just got to bang your head against a brick wall,” says Kurt Klaus, with a mischievous grin. And that’s precisely what the wiry character with the wide-awake eyes behind the glasses did. Around 40 years ago, during his time as head watchmaker with IWC, he developed a mechanical calendar that shows the date, day of the week, year in four digits and moon phase on the dial until 2499. Like the minute repeater and the tourbillon, the perpetual calendar is of the big complications and thus one of the greatest master strokes ever achieved by the luxury watch manufacturer from Schaffhausen.

With its many vagaries, the Gregorian calendar, which was based on the Julian calendar introduced under Julius Caesar, is a hurdle for any young child. One well-known method of remembering the lengths of the months involves reading them off on your knuckles. But knowing that the months have 28, 30 or 31 days is not enough: we need to add an extra “leap” day – the 29th of February – every four year to correct the deviation from the real solar year. Generations of watchmakers and inventors have racked their brains to develop a mechanical calendar consisting of cogs, levers, switch cams, springs and clicks that would replicate it.

The first such mechanisms were found inside huge astronomical clocks. From the 1920s onwards, they were a regular feature of pocket watches and, finally, of wristwatches. However, they were still extremely complicated and not very user-friendly. A perpetual calendar for a pocket watch, for example, consisted of over 200 parts, and each of its displays had to be set separately using push-buttons. “I’d always been annoyed by all these imperfections,” says Klaus, looking back.

The beginning of a chapter that was to mark a decisive change in IWC’s history came in the late 1970s, a time when the Swiss watch industry was in the throes of its most testing crisis ever. Electronic timepieces, whose tempo was determined by a quartz crystal and not an evenly oscillating balance, were mass-produced in Japan and flooding the world’s markets. The expertise amassed by watchmakers and timers through the course of many generations was suddenly superfluous. All the know-how relating to complex precision mechanisms that had been continuously perfected over the centuries was threatened with extinction from one day to the next.

But while many of his peers joined together to wail in unison about the situation, Klaus got down to work: in the mid-1970s, he created the first calendar for a magnificent open-face pocket watch, of which almost 100 were sold. “It became clear to me then that the only way IWC could set itself apart from the competition was with unusual timepieces like those,” he recalls. Success was the spur, and he continued to work away at his mechanisms, often during his own leisure time. He created displays for the moon phase or the signs of the zodiac and even came up with an unusual thermometer watch. Finally, he succeeded in persuading executive management under Günter Blümlein and Hannes Pantli to give the go-ahead for the development of a perpetual calendar for wristwatches.

Back then, calendars tended to be built into a particular movement, but Klaus wanted was to design a separate module he could integrate into different basic movements. With his calendar, he was also aiming to set new standards regarding simplicity and operation. And in keeping with the spirit of IWC’s founder F.A. Jones, Klaus the perfectionist was already thinking in terms of possible industrial production. He decided, therefore, to work with relatively simple shapes and as few parts as possible.

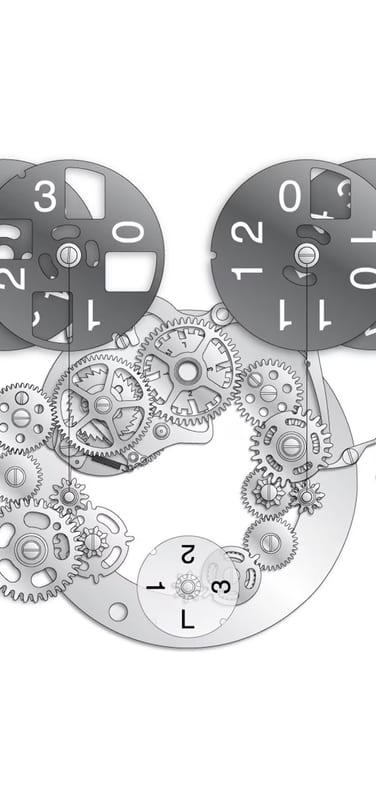

The basic idea was to use the date mechanism integrated into the basic movement as a source of power. A single switching impulse triggered during the night would activate an entire gear chain and advance the date, the day of the week and the moon phase displays. After a month had passed, the month indicator would likewise advance, followed by the decade indicator after ten years and the century display after a hundred. All evenly paced and perfectly synchronized.

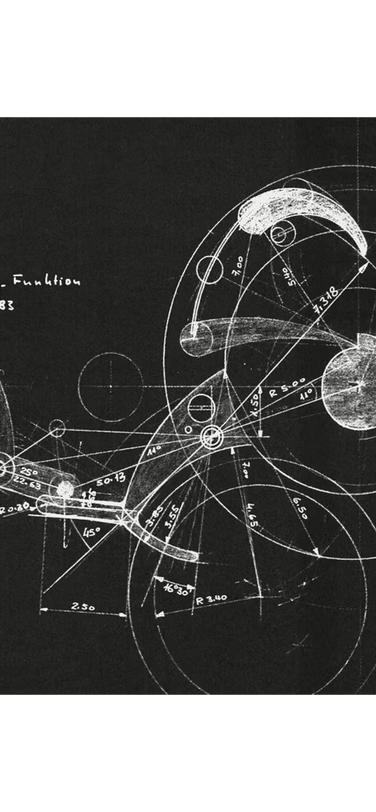

So much for theory. In practice, however, the undertaking turned out to be more complicated. In the course of long walks, Klaus sketched out the basic functions in his mind’s eye. On the drawing board, the shape and arrangement of the parts underwent continuous revision. “I constructed the entire mechanism on triangles, assigned coordinates to every position and carried out countless calculations,” he explains, recalling the intensive and at times frustrating design phase. Despite all the setbacks, he managed to complete three working prototypes just in time for the Da Vinci Chronograph Perpetual Calendar’s début at the 1985 Watch Show in Basel.

The way the mechanism — with just 81 parts — functions is unbelievably efficient. Every night, the basic movement causes the date advance lever to move. In response, a click advances the date wheel, with its 31 teeth, by one day. At the same time, another lever causes the star-shaped day-of-the-week wheel and moon phase display to move forward. A single tooth on the date wheel is longer than all the others: at the end of each month, it automatically advances the month cam, as it is known, by a single position.

At the same time, this cam is the centrepiece of the mechanical calendar programme. Running round its edge is a series of raised and indented sections, which provide information about the differing lengths of the months. It functions in a way similar to the punch cards from the days when computer technology was in its infancy. To ensure that the leap years are also part of the equation, the cam represents a full four-year cycle consisting of 48 months. A single recess – the one for the 29th of February – is, therefore, deeper than all the others.

In the shorter months, another mechanism comes into play. An additional click on the date advance lever rests on an eccentric that is connected directly to the date wheel. At the end of months with fewer than 31 days, it drops down from the eccentric to rest on a projection. “During the switching sequence, which takes place in the middle of the night, it advances all the days before the non-existent 31st of the month before the normal pawl comes into play and advances the date wheel by a single tooth,” says Klaus, describing one of the essential features of his design.

This additional mechanism is controlled indirectly by the month cam. In months with fewer than 31 days, a feeler arm connected to the date advance lever falls into a recess. The deeper the recess, the greater the radius through which the date advance lever moves. A long radius causes the additional pawl to be retracted slightly further and drops from the eccentric at the end of the month. “The protrusions and recesses on the month cam determine the different radii and whether and when the additional pawl comes into action,” says Klaus.

Several calendar mechanisms had already been invented in the past, but Klaus went a few steps further. Starting with the month wheel, which takes over the display of the calendar month on the dial, he integrated a transmission chain that led, successively, to a year wheel, a decade wheel and a century slide. The latter is moved through just 1.2 millimetres every 100 years. To put this in perspective: during the same period, a point on the balance rim theoretically covers a distance equal to 40 orbits of the Earth.

Kurt Klaus had thus hit upon a solution that was revolutionary in several respects. The most important new feature was the perfect synchronization of all the displays, from the date and day of the week through to the month and phase of the moon. “If the watch isn’t worn for a few days and stops, all the displays can be advanced and reset simply, one day at a time. For the first time, a perpetual calendar also came with a four-digit year display. Another new feature was the extremely precise moon phase display. Thanks to the accuracy of its transmission, it needs to be corrected by one day only after 122 years.

The Da Vinci Chronograph Perpetual Calendar proved to be a resounding success and marked a reversal in the history of IWC. Just a few years later, the Schaffhausen-based company unveiled its first Grande Complication. This watch marked IWC’s arrival at the pinnacle of haute horlogerie. The basic functional principles of the perpetual calendar watches, which is found today in the Portugieser and Pilot’s Watch families, have remained virtually unchanged since 1985. The mechanism comprises fewer than 100 parts and sets itself apart thanks to its uncompromising user-friendliness. It will need to be advanced manually by one day only in 2100, when, due to another quirk of Pope Gregory’s calendar, the leap year will be omitted.

IWC has continued to develop and slightly modify the calendar since its introduction. The design engineers at Schaffhausen created a version with a digital display for the date and month, for example, which is now also to be found in the Da Vinci, Portugieser, Ingenieur and Aquatimer families. Another new departure was a model with a double moon phase display, which also depicts the shape of the moon as seen from the southern hemisphere. None of these innovations, however, would ever have been possible without the conviction, the inventive spirit and persistence of a man who wasn’t afraid of banging his head against the wall: Kurt Klaus